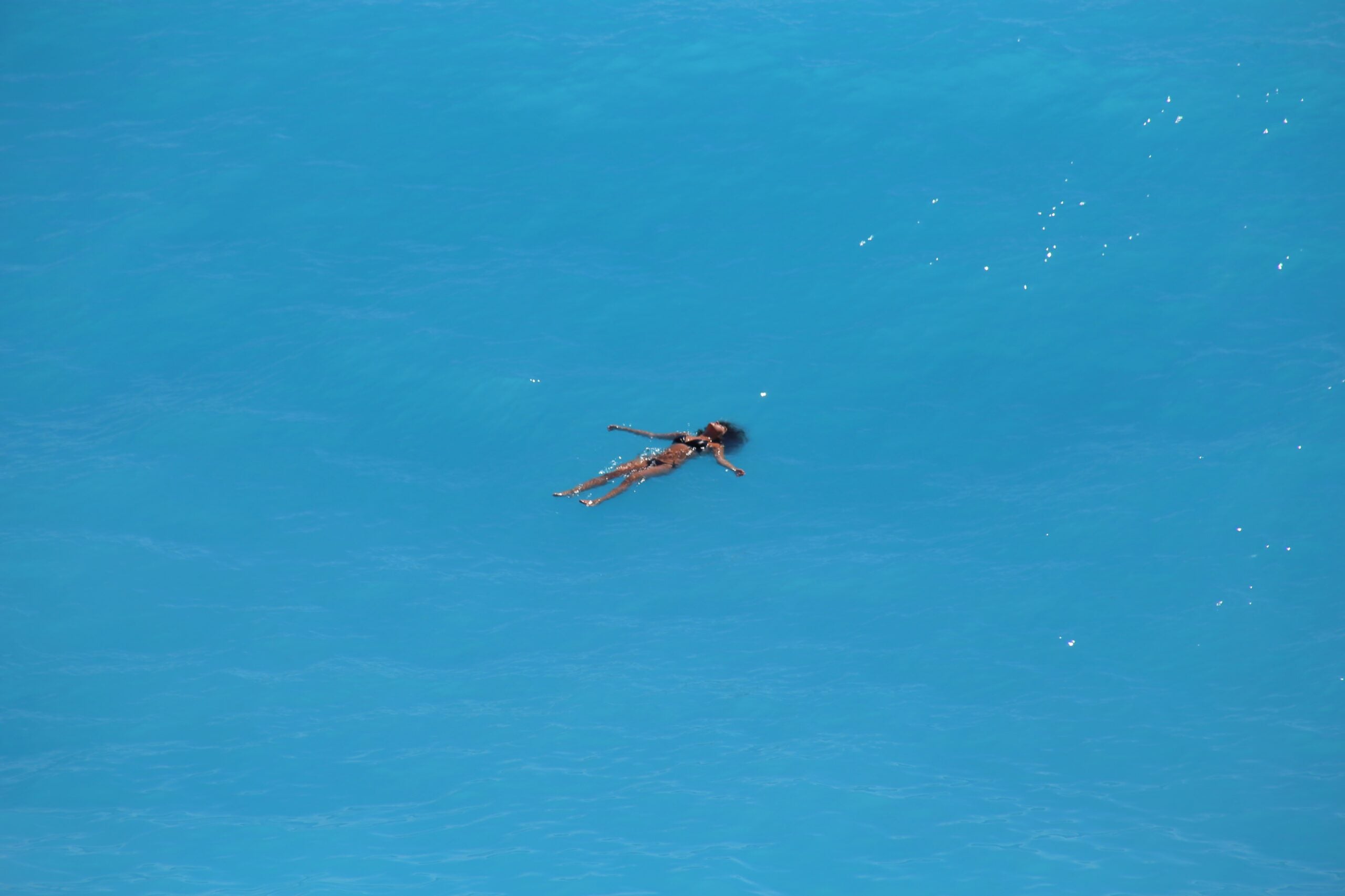

Troubled Waters: How Might Beauty Products Be Making Our Waterways Less Safe?

FROM VITA DAILY, BY AILEEN LALOR (LINK BELOW)

When beauty brands talk about clean beauty, it’s mostly in the context of what the products we apply might do to our skin; the theory is certain ingredients might be absorbed into our bloodstreams and cause hormonal issues and even cancer. What’s less discussed is the issue of runoff—what happens when the remnants of all those products go down the drain.

When beauty brands talk about clean beauty, it’s mostly in the context of what the products we apply might do to our skin; the theory is certain ingredients might be absorbed into our bloodstreams and cause hormonal issues and even cancer. What’s less discussed is the issue of runoff—what happens when the remnants of all those products go down the drain.

It’s something that preoccupies Maria Wodzinksa, co-founder of Toronto-based Stoic Beauty, and her business partner, Dr. Jolanta Wodzinksa, who is her mother and a PhD chemist. “For most of her career she worked in the pharmaceutical industry where anything that shows the potential for harm is cut off at the legs,” Maria explains. “I started doing some skincare development and my mother got curious. She looked into the data around biodegradability and accumulation and found that in the beauty industry, this is very under-researched and poorly regulated—that products at scale were going into water systems.”

How concerned should we be about that? “While we have knowledge gaps in the extent of the contamination and environmental harm chemicals present, we know enough to know there is a problem,” says Jennifer Lee, chief impact officer at Beautycounter. “Take PFAS as a recent headline chemical. These chemicals are highly persistent and ubiquitous to the environment and not only can pose harm to human health, emerging research points to their potential ecological toxicity.”

Lee explains there are many variables that go into how much of different chemicals might be found in the environment: how much of them and how often they’re released, how effectively water treatment plants can remove substances and how quickly they degrade in the environment, for example. One substance that we know is accumulating in the environment is plastic.

“Microplastics … have been found in 100 per cent of humans surveyed, according to recent research reported by National Geographic,” says Jayme Jenkins, co-founder of Everist, which makes water-free body and hair products. “The exact implication of this is unknown, but it’s not expected to be good.” Then there are ingredients like triclosan (an antimicrobial) that is toxic to some algae and fish, and oxybenzone, a sunscreen ingredient that is highly damaging to coral.

Beyond the immediate effects there are also impacts further down the line. “Persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic chemicals, or PBTs, are a particularly worrisome category of chemicals for downstream effects,” says Lee. “These chemicals persist in the environment; they do not readily break down. They bioaccumulate, meaning they build up in us and other living organisms faster than our bodies can remove them, and they are toxic.” Lee points out that PBTs have a disproportionate effect on some Indigenous communities because their diets are contaminated.

How do brands go about eliminating ingredients that might harm the environment? They typically take an “if in doubt, leave it out” approach and eschew ingredients derived from petroleum. “We avoid synthetic fragrances, colourants, silicones, parabens and so on, and choose organic ingredients where possible,” says Jenkins. Dr. Wodzinska says that at Stoic she uses the same approach as she took in the pharmaceutical industry to analyze risk/benefit ratio. “When talking about cosmetics, in my opinion, all ingredients that are used primarily to improve sensorial properties offer little benefit, hence any doubt as to their impact on human health or the environment would be a reason for me to eliminate them until the debate is resolved. This is, for example, why silicones are on our ‘no’ list, as they are often used for slick and matte textures, but biodegradability is an issue.”

Eliminating potentially harmful ingredients means brands also have to approach formulation in an especially creative way. “When it comes to preservatives, we think about hurdle testing, which means that instead of hitting microbes hard with a formaldehyde we create multiple hurdles, like the pH is unfriendly and the viscosity are unfriendly,” says Maria. “Those kinds of heavy-duty ingredients are really not necessary.”

Beyond formulation, eliminating or reducing plastic usage is important. “A major choice for us was to avoid plastic tubes for our product—even though they would be cheaper and easier to manufacture with—instead choosing 100 per cent recycled and recyclable aluminium tubes,” Jenkins says. “New research is constantly emerging, but already the data is clear: the plastic problem is pervasive and it’s not just plastic going to landfill, it’s the credit card’s worth of plastic we consume every week.”

How can you feel confident that the beauty products you are using will be safe for waterways—as well as other items like household-cleaning products? It’s not something companies can be certified for. You may be safer buying from brands that label themselves “clean,” though that’s not the case for everyone. Companies should be transparent about what’s in their products; Stoic, Beautycounter and Everist all have extremely detailed information on their websites. You can also reach out to businesses to find out how they’re thinking about water. But, ultimately, experts believe there needs to be better government regulation and oversight in order to protect our precious water. “By 2050, water will become the most valuable commodity on earth,” says Maria. “So I think it’s time to start raising this alarm.” —Aileen Lalor